A VERY HAPPY EASTER, RAMADAN MUBARAK, and CHAG KASHER VE SAMEACH! I hope everyone (of whatever belief) has had a wonderful time this weekend/season with family, friends and rejoicing in the spirit of life.

I was of two minds about posting this particular excerpt—it is a slight spoiler—but it seemed particularly appropriate for Easter.

[Excerpt from UNTITLED BOOK TEN, Copyright © 2023 Diana Gabaldon]

In which Jamie and William are crossing a patch of wild land. I’m not telling you where they’re going or why. <g> (NB: Things in square brackets are places where something—like a particular bit of Gaelic—will be filled in later.) And “crined” is not a typo; it’s a Scots word, meaning “shrunken” or “crumpled”.

Jamie felt the crawling and slapped a hand hard over his ribs. The slap numbed his flesh for a moment, but the instant it passed, he felt the tickle again—and in several places at once, including his—

Jamie felt the crawling and slapped a hand hard over his ribs. The slap numbed his flesh for a moment, but the instant it passed, he felt the tickle again—and in several places at once, including his—

“[Gaelic curse]! Earbsa!”

He ripped the flap of his breeks open and shoved them down over his legs, in time to catch the tick crawling toward his balls before it sank its fangs in him. He snapped it away with a flick of a fingernail and jerked the collar of his sark up over his head.

“Dinna go through the bushes!” he shouted from inside the shirt. “They’re alive wi’ ticks!” William said something, but Jamie didn’t catch it, his head enveloped in the heavy hunting shirt. His skin was afire between the sweat and the crawling.

He yanked the sark off and flung it away, scratching and slapping himself. Ears now free, he heard the next thing William said. Clearly.

“Oh, Jesus.” It wasn’t much more than a whisper, but the shock in it froze Jamie with realization. By reflex, he bent, arm stretched out for his shirt, but it was too late. Slowly, he stood up again. A tick was trundling over the curve of his breast, just above the cutlass scar. He reached to snap it off, and saw that his fingers were trembling.

He clenched his fist briefly to stop it, then bent his head, picked off three more of the wee buggers on his neck and ribs, then scratched his arse thoroughly, just in case, before pulling up his breeks. His heart was racing and his wame was hollow, but there was naught to do about it. He took a deep breath and spoke calmly, without turning around.

“D’ye see any more of them on my back?”

A moment’s silence, and a let-out breath. Crunching footsteps behind him and a faint sense of warmth on his bare back.

“Yes,” William said. “It’s not moving, I think it’s dug in. I’ll—get it off.”

Jamie opened his mouth to say no, but then closed it. William seeing his scars close to wasn’t like to make matters worse. He closed his eyes instead, hearing the shush of a knife being drawn from its sheath. Then a large hand came down on his shoulder, and he felt his son’s breath hot on the back of his neck. He barely noticed the prick of the blade or the tickle of a drop of blood running down his back.

The hand left his shoulder, and to his surprise, he missed the comfort of the touch. The touch came back an instant later, when William pressed a handkerchief below his shoulder blade, to stop the bleeding.

A moment, and the cloth lifted, tickling his back. He felt suddenly calm, and put on his shirt, after shaking it hard to dislodge any hangers-on.

“Taing,” he said, turning to William. “Ye’re sure ye’ve none on ye?”

William shrugged, face carefully expressionless.

“I’ll know soon enough.”

They walked on without speaking until the sun began to touch the trees on the highest ridge. Jamie had been looking out for a decent spot to camp, but William moved suddenly, nodding toward a copse of scrubby oaks near the top of a small hillock to the right.

“There,” he said. “Cover, we’ll have good sight of the trail, and there’s water coming down the side of that gravelly bit.”

“Aye.” Jamie turned in that direction, asking after a moment, “So, was it the army taught ye castrametation, or Lord John?”

“A bit of both.” William spoke casually, but there was a tinge of pride in his voice, and Jamie smiled to himself.

They made camp—a rudimentary process involving naught more than gathering wood for a fire, fetching water from the rill and finding stones flat enough to sit on. They ate the last of the bread and cold meat, and a couple of small, mealy apples pitted with the knots of insect chewing, and drank water, as there was nothing else.

There was no conversation, but there was an awareness between them that hadn’t been there before. Something different to their usual polite awkwardness, but just as awkward.

He wants to ask, but doesna ken how. I dinna want to tell him, but I will. If he asks.

As the dark deepened, Jamie heard a distant sound and turned his head sharply. William had heard it too; rustling and shuffling below, and now a chorus of grunting and loud guttural noises that made it clear who the visitors were.

He saw William turn his head, listening, and reach down for his rifle.

“At night?” Jamie asked. “There’s a dozen o’ them at least. And if we killed one without being torn to bits by the rest, we’d leave most of it to the crows. Ye really want to butcher a hog just now?”

William straightened up, but was still listening to the pigs below.

“Can they see in the dark, do you know?”

“I dinna think they’d be walkin’ about now, if they couldn’t. But I dinna think their sight is any better than ours, if as good. I’ve stood near a herd o’ them, nay more than ten yards away—upwind, mind—and they didna ken I was there until I moved. There’s naught amiss wi’ their ears, hairy as they are, and anything that can root out trubs has a better sense o’ smell than I have.”

William made a small noise of amusement, and they waited, listening, ‘til the sounds of the wild hogs faded into the growing night sounds—a racket of crickets and shrilling toads, punctuated by the calling of night birds and owl-hoots.

“When you lived in Savannah,” William said abruptly. “Did you ever encounter a gentleman named Preston?”

Jamie had been half-expecting a question, but not that one.

“No,” he said, surprised. “Or at least I dinna think so. Who is he?”

“A… um… very junior undersecretary in the War Office. With a particular interest in the welfare of British prisoners of war. We met at a luncheon at General Prevost’s house, and then later that evening, to discuss… things… in more detail.”

“Things,” Jamie repeated, carefully.

“Conditions of prisoners of war, mostly,” William said, with a brief wave of the hand. “But it was from Mr. Preston that I discovered that my father had once been governor of a prison in Scotland. I hadn’t known that.”

Oh, Jesus…

“Aye,” Jamie said, and stopped to breathe. “A place called Ardsmuir. That’s where I first became acquainted—” He stopped, suddenly recalling the whole truth of the matter. Do I tell him that? Aye, I suppose I do.

“Aye, well, I met your father there, that’s true—though I’d met him some years before, ken. During the Rising.”

He felt a sudden prickle in his blood at the memory.

“Where?” William asked, curiosity clear in his voice.

“The Highlands. My men and I were camped near the Carryarick Pass—we were lookin’ out for troops bringin’ cannon to General Cope.”

“Cope. I don’t believe I recall the gentleman…”

“Aye, well. We—disabled his cannon. He lost the battle. At Prestonpans, it was.” Despite the present situation, there was still a deep sense of pleasure at the recollection.

“Indeed,” William said dryly. “I hadn’t heard that, either.”

“Mmphm. It was your uncle, his grace, that was in charge of bringin’ the cannon, and he’d brought along his young brother to have a, um, taste of the army, I suppose. That was Lord John.”

“Young. How old was he?” William asked curiously.

“Nay more than sixteen. But bold enough to try to kill me, alone, when he came across me sittin’ by a fire with my wife.” Despite his conviction that this conversation wasn’t going to end well, he’d started, and he’d finish it, wherever it led.

“He was sixteen,” Jamie repeated. “Plenty of balls, but no much brain, ken.”

William’s face twitched a little at that.

“And how old were you, may I ask?”

“Four-and-twenty,” Jamie said, and felt a rush of such unexpected feeling that it choked him. He’d not thought of those days in many years, would have thought he’d forgotten, but no—it was all there in a heartbeat: Claire’s face in the firelight and her flying hair, his passion for her eclipsing everything, his men nearby, and then the moment of startlement and instant rage and pummeling a stripling on the ground, the dropped knife glinting on the ground beside the fire.

And everything else—the war. Loss, desolation. The long death of his heart.

“I broke his arm,” he said abruptly. “When he attacked me. He wouldna speak, when I asked where the British troops were, but I tricked him into saying. Then I told my men to tie him to a tree where his brother’s men would find him… and then we went to deal wi’ the cannon. I didna see his lordship again until—” He shrugged. “A good many years later. At Ardsmuir.”

William’s face was clearly visible in the firelight, and Jamie could plainly see interest war with caution, while the lad— Christ, he’s… three-and-twenty? Older than me when…

“Did he do it?” William asked abruptly.

“What?”

William made a small movement of one hand and nodded toward him.

“Your… back. Did Lord John do that… to you?”

Jamie opened his mouth to say no, for all his memory had been focused on Jack Randall, but of course…

“Part of it,” he said, and reached for his canteen on the ground, avoiding William’s eye. “Not that much.”

“Why?”

Jamie shook his head, not in negation, but trying to organize his thoughts.

“I made him,” he said, wondering What’s the matter wi’ me? It’s the truth, but—

“Why?” William asked again, in a harder tone of voice. Jamie sighed deeply; it might have been irritation, but it wasn’t; it was resignation.

“I broke a rule and he had me punished for it. Sixty lashes. He didna have any choice, really.”

William gave his own deep sigh and it was irritation.

“Tell me or don’t,” he said, and stood up, glaring down at Jamie. “I want to know, but I’m not going to drag it out of you, God damn it!”

Jamie nodded, his immediate feeling of relief tainted by memory. His back itched as though millions of tiny feet were marching over it, and the tiny wound burned. He sighed.

“I said I’d tell ye whatever ye wanted to know, and I will. The Government outlawed the possession of tartan. A wee lad in the prison had kept a scrap of his family’s tartan, for comfort—it wasna likely that any of us would see our families again. It was found, and Lord John asked the lad was it his. He—the lad, I mean—was no but fourteen or fifteen, small, and crined wi’ cold and hunger. We all were.” Memory made him stretch out his hands toward the fire, gathering the warmth.

“So I reached over his shoulder and took the clootie and said it was mine,” he finished simply. “That’s all.”

Please visit my official Book Ten webpage to read more excerpts from this book.

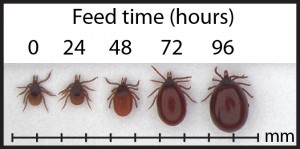

Photo courtesy of the Center for Disease Control.

This excerpt from Book Ten was originally posted on my official Facebook page on April 7, 2023. And on Twitter/X.

Many thanks to Donna Andrews for letting my Webmistress, Loretta, know that this excerpt was missing from my website! In Loretta’s defense, April 2023 was a during a difficult time for her (healthwise).

This excerpt was also posted as one of my blog entries on March 29, 2024, which allows public web comments to be submitted.