I’ll be at the Historical Novel Society conference this weekend in St. Petersburg, Fl.–where I will, among other things, be Mistress of Ceremonies at the Saturday Late-Night Sex-Scene Readings. [g]

Now, in previous years, we had only a half-dozen or so hardy souls willing to get up and read their naughty scenes in front of the banquet audience…but _this_ year, we had more than forty volunteers! (Must be the influence of the Fifty Shades books, I suppose. Suddenly it’s fine to read pornography in public, so why not scenes of literary merit with sexual content, hey?)

I could only take a few of the willing applicants, because you really can’t expect people to sit through more than an hour of sex scenes, no matter how well written…but how to choose?

Well, basically, I took the two men who volunteered, because it’s hard to find men who will do that

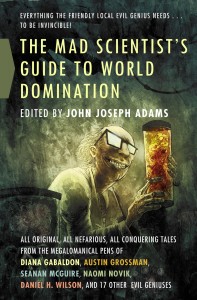

So…I offered those who didn’t make the roster the opportunity to have their scenes posted here on my Facebook page, for the enjoyment of souls of a discriminating nature–who might, should they find the material interesting, go and look for the books of the person who wrote a good scene.

Several bold writers accepted this offer

FOR THE MOMENT, though–here’s a brief taste of the less-rowdy side of the conference, with a Q&A I did with Jenny Barden (last year’s HNS organizer, and a brilliant job she did, too!), whose new book, MISTRESS OF THE SEA, is just coming out in the US in paperback:

Diana Gabaldon takes time out from packing for the HNS Conference in Florida to quiz fellow delegate Jenny Barden about her paperback debut, Mistress of the Sea

DG: What drew you to Francis Drake, Jenny, and why this particular episode?

JB: Sir Francis Drake is one of the best loved English heroes. He spearheaded the attacks against the Spanish at sea which led to the gradual erosion of their global dominance during the Elizabethan era and culminated in the defeat of the Spanish Armada. In the episode that forms the backdrop to Mistress of the Sea, Drake managed to strike where the Spanish least expected and where it hurt most: at their bullion supply from South America. I loved the fact that Drake achieved this feat with so few men; only 15 English mariners accompanied him on the last decisive raid, and he did it in alliance with runaway African slaves whom he honoured as loyal friends. Drake also teamed up with French Huguenot privateers; plainly, he didn’t hold the conventional prejudices of his age! He was patriotic, recklessly brave, and totally determined to the point of ruthlessness. (He scuttled his brother’s ship to stop his men going back to England too soon.) I find that kind of passionate zeal and readiness to go the edge and beyond really fascinating in this age of moderation and compromise. Drake was definitely not pc! But he kept going in the face of successive setbacks and defeats. More than half his crew died during the campaign, including two of his younger brothers, but Drake never gave up. In that respect, if no other, I consider him an excellent role model for writers!

DG: Tell me about the love-interest, Will. What does Ellyn see in him?

DG: Tell me about the love-interest, Will. What does Ellyn see in him?

JB: Will is a maverick. He’s ruggedly good looking in a Sean Bean kind of way (and if you’re not familiar with Sean Bean then think of a taller, chiseled Brad Pitt!). He’s also a charmer with the ladies, and there’s an immediate physical attraction between him and Ellyn. The rapport between them intellectually takes much longer to develop because of their social inequality. (Will is a craftsman, disowned by his father, who has run away to sea, while Ellyn is the daughter of a wealthy merchant with high hopes of an advantageous marriage.) Ellyn considers Will to be a bit of an upstart at first, but he also fascinates her with his tales of adventure. He has the allure of the high seas, travel to far flung places, escape and everything she secretly longs for. He’s also a puzzling character with a dark side, driven by bloodlust and a desire for vengeance for the loss of his brother at the hands of the Spaniards (a mirror of the vengeance that motivated Drake as a matter of historical fact). Will is a man of action, and Ellyn is entranced by him to the point at which she takes action herself, steps into her brother’s shoes, and follows Will aboard Drake’s ship…

DG: I found Ellyn’s feelings for her father very touching and well-drawn. What was the inspiration for that relationship?

JB: The inspiration for the relationship between Ellyn and her father came directly from my own experience. My dad died some years ago, alas – long before Mistress of the Sea was published. I was a bit of a tearaway tomboy, and was constantly in a ding-dong battle of wits with my father, determined to have my own way and prove that I could be just as good as any boy. My father had a rather Elizabethan approach to gender which was most definitely not one of equality! He was wonderful, but, in his judgement, girls were never going to achieve as much as men, and it was storing up trouble to extend their aspirations beyond being good wives and mothers. (Though higher education was not to be discouraged, it would probably be a waste in the long run – but that didn’t stop him taking great pride in my achievements!). In this respect, creating the character of Nicholas Cooksley and the tension between him and Ellyn was easy; I simply tapped into my memories, though, both in reality and in fiction, there was much more to the father-daughter bond and conflict. My father and I loved one another deeply but could never quite accept the other’s point of view.

Las Cruces trail – an extension of the Camino Real

DG: It is an exotic setting. What did you most enjoy writing about that?

JB: The Caribbean, and Panama in particular, is a superb location for a story. I adored doing the ‘on the ground’ research, picking up as much of the Camino Real as I could find, by which I mean the old ‘Royal Road’ along which bullion from Peru was transported overland by mule-train, from the City of Panama on the Pacific, to Nombre de Dios leading to the Atlantic. This traffic in bullion went on for well over a hundred years. I found places where the constant passage of hooves had worn hollows in the stones leading to overgrown pathways in the depths of the jungle. From idyllic coral atolls to the summits of forest-clad mountains with precipitous drops and stunning views; from scuba diving off Kuna Yala to traipsing through rainforest in nearly 100% humidity searching for traces now largely lost under the Panama Canal. I loved finding where the adventure actually happened. In those places, in my mind, the characters began to speak and the story came alive.

DG: What do you think you would have found most difficult about living in this time?

JB: Not having a nice hot bath, or even a shower, after a tiring day would have been fairly miserable. I’d have gone to bed each night sweaty, dirty and scratching fresh insect bites (ugh!)

DG: What research materials did you find most useful?

JB: The first hand accounts, both English and Spanish, were the most useful resources for me. The best account of Drake’s raid comes from Sir Francis Drake Revived, compiled by his preacher from the testimony of his crew. On the Spanish side, we have the documents from the Archives of the Indies at Seville, translated by Irene Wright and published by the Hakluyt Society. Of the many biographies about Drake, I found John Sugden’s the most readable. Then I have a few personal favourites in terms of quirky reference material, such as Old Panama and Castillo Del Oro by CLG Anderson with some really good pictures of Panama before the Chagres River was dammed to make the Canal. I also found living history exhibits such as the Golden Hinde reconstruction near London Bridge very helpful. There’s no better way of appreciating how damp, cramped and uncomfortable life would have been on a long voyage aboard an Elizabethan sailing ship than spending three hours in the hold giving talks back to back!

DG: I gather the next book is finished! – congratulations! Is it in the same setting? What are we allowed to know?

JB: Your congratulations are very much appreciated, thank you. The next book moves north quite a bit to the Island of Roanoke in what is now North Carolina. The story is set against the backdrop of the ‘Lost Colony’: the first attempt to found a permanent English settlement in America. I’m sure that, when I first began looking into this, you knew a lot more about it than I did, because everyone in the States seems to have heard of the ‘Lost Colony of Roanoke’, and almost no one has come across it here in England. Whilst we’re taught about the Elizabethan era at junior school, we’re generally not told about this remarkable endeavour and enduring mystery. I’ve really enjoyed the research, particularly since new evidence came to light during the course of writing the novel; I’ve had fun working that in! The story follows my fictional characters, Kit Doonan (Will’s brother) and Emme Fifield, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen, who embarks on the voyage with a secret brief from the Queen’s spymaster, Walsingham, in order to escape the predatory attentions of the son of the Duke of Somerset. (The Lost Duchess will be published in the UK on 7 November.)

DG: It will be great to catch up again at the HNS conference in Florida. What are you most looking forward to?

JB: I can’t wait for the Conference; it’s going to be a ball! I’m most looking forward to seeing you again and catching up with my HNS friends in the US, and particularly to the fabulous *not-to-be-missed* Saturday Night Sex Scene Readings which you’ll be hosting. (I’m still recovering from the San Diego experience 2 years ago!)

Thank you so much for asking me these questions, Diana, and for your interest in Mistress of the Sea. The novel is not yet available in the States, but I will be bringing a few rare advance copies for enthusiasts at the Conference!

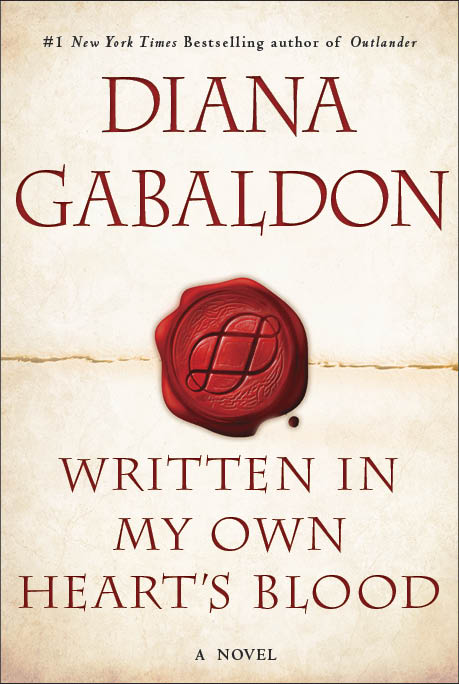

Wishing you every possible success with the next Outlander – can’t wait for that either!