May 25, 2022

All my books have an internal geometric or natural shape that emerges in the course of the work, and once I’ve seen it, the writing goes much faster. I may have no idea exactly what happens, what’s said, etc.—but I do know approximately what the missing pieces look like (e.g., I need a scene here that involves these three people, and it has a sense of rising tension and a conclusion that will lead into that scene over there…).

All my books have an internal geometric or natural shape that emerges in the course of the work, and once I’ve seen it, the writing goes much faster. I may have no idea exactly what happens, what’s said, etc.—but I do know approximately what the missing pieces look like (e.g., I need a scene here that involves these three people, and it has a sense of rising tension and a conclusion that will lead into that scene over there…).

These internal shapes are normally invisible to the reader—who isn’t looking for them in the first place—but if pointed out, the reader can certainly see them. Here are the shapes of each book in my Outlander series of novels:

I. OUTLANDER — Three Overlapping Triangles

My first book, OUTLANDER, is shaped like three overlapping triangles: the action rises naturally toward three climaxes: Claire’s decision at Craig na Dun to stay in the past, Claire’s rescue of Jamie from Wentworth, and her saving of his soul at the Abbey.

My first book, OUTLANDER, is shaped like three overlapping triangles: the action rises naturally toward three climaxes: Claire’s decision at Craig na Dun to stay in the past, Claire’s rescue of Jamie from Wentworth, and her saving of his soul at the Abbey.

II. DRAGONFLY IN AMBER — Dumbbell

DRAGONFLY is shaped like a dumbbell (no, really <g>). The framing story, set in 1968 (or 1969; there’s a copyediting glitch in there that has to do with differences between the U.S. and U.K. editions of OUTLANDER, but we won’t go into that now), forms the caps on the ends of the dumbbell. The first arc of the main story is the French background, the plots and intrigue (and personal complications) leading toward the Rising. Then there’s a relatively flat stretch of calm and domestic peace at Lallybroch, followed by the second major arc, the Rising itself. And the final end-cap of the framing story. All very symmetrical.

DRAGONFLY is shaped like a dumbbell (no, really <g>). The framing story, set in 1968 (or 1969; there’s a copyediting glitch in there that has to do with differences between the U.S. and U.K. editions of OUTLANDER, but we won’t go into that now), forms the caps on the ends of the dumbbell. The first arc of the main story is the French background, the plots and intrigue (and personal complications) leading toward the Rising. Then there’s a relatively flat stretch of calm and domestic peace at Lallybroch, followed by the second major arc, the Rising itself. And the final end-cap of the framing story. All very symmetrical.

III. VOYAGER — Braided Horse-Tail

VOYAGER looks like a braided horse-tail: the first third of the book consists of a three-part braided narrative: Jamie’s third-person narrative runs forward in time; Claire’s first-person narrative goes backward in time (as she explains things to Roger and Brianna), and Roger’s third-person narrative sections form the present-time turning points between Claire’s and Jamie’s stories. After Claire’s return to the past, though, the story then drops into the multi-stranded but linear first-person narrative (moving forward) that we’re used to.

VOYAGER looks like a braided horse-tail: the first third of the book consists of a three-part braided narrative: Jamie’s third-person narrative runs forward in time; Claire’s first-person narrative goes backward in time (as she explains things to Roger and Brianna), and Roger’s third-person narrative sections form the present-time turning points between Claire’s and Jamie’s stories. After Claire’s return to the past, though, the story then drops into the multi-stranded but linear first-person narrative (moving forward) that we’re used to.

IV. DRUMS OF AUTUMN — Curving, Leafy Stem with Rose

DRUMS… well, that one’s a little more free-form, but it does have a shape. It’s shaped like a curving, leafy stem, with a big, showy rose at the end, but with two side-stems, each with a large bud (these being Roger and Brianna’s independent part of the story, and the Jocasta/Hector/Ulysses/Duncan/Phaedre part).

V. THE FIERY CROSS — Rainbow or Fireworks

THE FIERY CROSS looks either like a rainbow or a shower of fireworks, depending how you want to look at it. <g> There are a number of separate storylines that arc through the book—but every single one of them has its origin and root in that Very Long Day at the Gathering where the book begins. Each storyline then has its own arc, which comes down at a different point toward the end of the book.

THE FIERY CROSS looks either like a rainbow or a shower of fireworks, depending how you want to look at it. <g> There are a number of separate storylines that arc through the book—but every single one of them has its origin and root in that Very Long Day at the Gathering where the book begins. Each storyline then has its own arc, which comes down at a different point toward the end of the book.

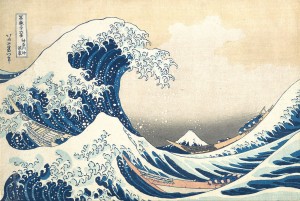

VI. A BREATH OF SNOW AND ASHES — Great Wave

For BREATH, think of a great wave, such as a tsunami in the ocean.

Well, probably you’ve seen that very well-known Hokusai print, shown at right, titled “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa.” When I happened to see this print while assembling the chunks for this book, I emailed my agent in great excitement, to tell him I’d seen the shape of the book. “It looks like the Great Wave,” I said. “Only there are two of them!” <g>

Well, probably you’ve seen that very well-known Hokusai print, shown at right, titled “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa.” When I happened to see this print while assembling the chunks for this book, I emailed my agent in great excitement, to tell him I’d seen the shape of the book. “It looks like the Great Wave,” I said. “Only there are two of them!” <g>

Notice, if you will, the little boats full of people, about to be swamped by the wave—these are the characters whose fate is affected by the onrush of events. And in the middle of the print, we see Mt. Fuji in the distance, small but immovable, unaffected by the wave. That’s the love between Claire and Jamie, which endures through both physical and emotional upheaval. (The waves are the escalating tides of events/violence that remove Claire and Jamie from the Ridge.)

VII. AN ECHO IN THE BONE — Caltrop

The shape of ECHO is a caltrop.

The shape of ECHO is a caltrop.

[pause]

OK, normally I’d make y’all look it up <g>, but the only person to whom I announced this revelation (husband, literary agents, editors, children) who already knew what a caltrop is, was my elder daughter (who is unusually well-read). So, all right—

Wikipedia defines the caltrop as “an area denial weapon made up of two or more sharp nails or spines arranged in such a manner that one of them always points upward from a stable base. Historically, caltrops were part of defenses that served to slow the advance of troops, especially horses, chariots, and war elephants, and were particularly effective against the soft feet of camels.” Caltrops are also called “foot spikes” for obvious reasons. An ancient Roman caltrop is shown in the image from Wikipedia.

Nasty-looking little bugger, isn’t it? (And if you think this image presages something regarding the effect of this book, you are very likely right.)

VIII. WRITTEN IN MY OWN HEART’S BLOOD – Octothorpe

Originally I wanted an octopus on the cover of MOBY— both because I really like octopuses and because of the symbolism (there are eight major characters whose stories I’m telling through this book— and it is the eighth book in my Outlander series, after all), there were certain technical issues that made that difficult. My husband—never a big fan of the octopus concept—asked whether I could think laterally; surely there were other ways to get an “8” onto the cover.

Originally I wanted an octopus on the cover of MOBY— both because I really like octopuses and because of the symbolism (there are eight major characters whose stories I’m telling through this book— and it is the eighth book in my Outlander series, after all), there were certain technical issues that made that difficult. My husband—never a big fan of the octopus concept—asked whether I could think laterally; surely there were other ways to get an “8” onto the cover.

So I thought. And almost at once, the word “octothorpe” sprang to mind. I’ve always liked the word, and it certainly was appropriate (you may or may not recognize it in its Very Artistic form here—but it’s the lowly hashtag, or pound sign (#)), as it not only has eight points (and eight “fields” of empty space surrounding it; one explanation of its origin is that it was a symbol on old English land documents for a farm surrounded by eight fields), but is a printing character—and the content of the book does indeed have a certain amount about the printer’s trade in colonial America during the Revolution.

IX. GO TELL THE BEES THAT I AM GONE — Snake

For BEES, book nine in my Outlander series, the main shape is a snake. It glides, it coils, it slithers, it climbs (and then drops out of a tree on you), it turns back on itself at the same time it goes forward, it has occasional bulges where it’s swallowed something large… and it has fangs.

For BEES, book nine in my Outlander series, the main shape is a snake. It glides, it coils, it slithers, it climbs (and then drops out of a tree on you), it turns back on itself at the same time it goes forward, it has occasional bulges where it’s swallowed something large… and it has fangs.

A honeycomb has a six-sided shape and represents the six main characters (or pairs) whose stories we’re following in BEES; the internal, cellular structure, if you will.

X. BOOK TEN (As yet untitled) — To Be Determined

Since I am working on this book at present, the shape for BOOK TEN hasn’t revealed itself yet. Stay tuned…

More on Shapes…

I’ve explained a little before, about how I write: to wit, not with an outline, and not in a straight line. <g> I write in bits and pieces, doing the research more or less concurrently with the writing (meaning that assorted bits of plot or new scenes may pop up unexpectedly as the result of my stumbling across something too entertaining to pass up).

I’ve explained a little before, about how I write: to wit, not with an outline, and not in a straight line. <g> I write in bits and pieces, doing the research more or less concurrently with the writing (meaning that assorted bits of plot or new scenes may pop up unexpectedly as the result of my stumbling across something too entertaining to pass up).

In the image at right, I was busy writing in my back yard a few years ago, and kept company by my dogs. Photo by my husband, Doug.

As I work, some of these bits and pieces will begin to stick together, forming larger chunks. For example, I’ll write a scene, and realize that it explains why what happened in a scene written several months ago happened. Ergo, the later scene probably ought to precede the first, already-written scene. So I haul both scenes into the same document, read through this larger chunk, and at that point, sometimes will see what has to happen next. (Sometimes not.) If so, then I can proceed to write the next bit. If not, I go look for another kernel (what I call the bits of inspiration that offer me a foothold on a new scene), and write something else.

Anyway, this process of agglomeration continues, and I begin to see the underlying patterns of the book. I get larger chunks. And all the time, I’m evolving a rough timeline in my head, against which I can line up these chunks in rough order (e.g., the battle of Saratoga was actually two battles, fought by the same armies on the same ground. But the dates of those battles are fixed: September 19th and October 7th, 1777. Some specific historical events occurred and specific historical persons were present in each of those two battles. Ergo, if I have assorted personal events that take place in the fictional characters’ lives, and various scenes dealing with those, I can tell that logically, X must have taken place after the first battle, because there’s a wounded man in that scene, while Y has to take place after the second battle, because the death of a particular person (who died in the second battle) precipitates Y. Meanwhile, Z clearly takes place between the battles, because there’s a field hospital involved, but there’s no fighting going on. Like that.)

Now, at a certain point in this chunking process, I discern the underlying “shape” of the book. This is Important.

All my books have a shape, and once I’ve seen what it is, the book comes together much more quickly, because I can then see approximately what-all is included, how it’s organized, and where the missing pieces (most of them, anyway) are.

More About My Books and Writing

See my webpage “One Word Speaks Volumes,”, to learn the single words that represent the themes in each of my Outlander novels.

And if you want to know more about how I write (my writing process and what I do), explore my Writer’s Corner (What I Do) resource at:

http://www.dianagabaldon.com/resources/what-i-do/

On May 30, 2022, information on this webpage was also posted as a blog entry with the same title.

Information on this page was first posted as “The Shape of Things,” one of my blog entries from 2018.

An earlier version is also included in THE OUTLANDISH COMPANION, VOLUME TWO, published in 2015.

I posted some of the information on shapes on the LitForum, as well.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 25, 2022 at 7:00 p.m. (Central Time) by Diana Gabaldon or Diana’s Webmistress.