Homer!

Well, we are once again a dogged household. We’ve been without a dog–for the first time in thirty-odd years–since our aged Molly (she of the gruesome post-mortem encounter with coyotes) succumbed to congestive heart failure at the age of sixteen or so, a few months ago. I’d wanted a smooth standard dachshund like my beloved Gus, if I could find one; most breeders these days seem to supply only mini-dachshunds or the occasional longhaired or wire-haired variety.

I’d been looking for a while, when I came across Kristin Cihos-Williams’s Alphadachs breeder listing online. On impulse, I called, got Kristin at once, and learned that she was sitting at home with a very pregnant dachshund named Lily, who was due that very day. We hit it off, and stayed in communication over the next three or four months, with the end result that our son and I drove to Indio on New Year’s Day to pick up one of the puppies from this litter (Kristin lives in Temecula, CA, but was at a dog-show in Indio, which is substantially closer to Phoenix).

It’s a four-hour trip from Phoenix to Indio, but the eight-hour drive was well worth it.

[Hmm. I tried to upload three photos of Homer here, but not working for some reason. Will try again tomorrow–gotta go to bed now. [yawn].]

ENCHILADAS

Copyright © 2009 Diana Gabaldon

My father was always one to recognize both merit and shortcomings. Consequently, while he was often generous with praise, all his compliments came with a “BUT…” attached. “This is wonderful, BUT…”

In fact, I remember only three unqualified compliments from him. Twenty years ago, he told me that my swimming stroke was perfect. Fifteen years ago, he told me that my children were beautiful. And on Christmas day ten years ago, he told me that my enchiladas were as good as his.

That Christmas Day was the last time I saw him. But he’ll always be with me, in the pull of water past my arms, in the faces of my children–and in the smell of garlic and chile, floating gently through the air of my kitchen.

*************

For them as don’t know, an enchilada is an item of traditional Mexican food, composed of a tortilla (mostly corn tortillas) rolled into a cylinder around some type of filling (traditionally cheese, but can be anything from chicken or beef to spinach, mushrooms, and seafood, particularly in nouveau Southwest or turista restaurants), covered with a spicy sauce, and baked. (Some restaurants don’t bother rolling their enchiladas, and just sprinkle cheese and fillings between flat tortillas, but we Do Not Approve.)

The traditional (cheese) form requires:

Garlic (one head)

olive oil (enough to cover the bottom of a large saucepan)

flour (a few tablespoons)

canola oil (or other light cooking oil) – enough to fill a small frying pan halfway

white or yellow onion – one

cheddar cheese – a pound will make 10-12 enchiladas

corn tortillas – these come in packages of 12, or three dozen. If you have more than two people coming to dinner, get three dozen. You can always make home-made tortilla chips out of the extras.

tomato sauce – three small cans

red chili (in any usable form; puree, frozen, powdered, or already mixed with the tomato sauce, which is my preferred variety; I use El Pato brand tomato sauce, which has the chili already in it)

I’m not giving quantities as such, because you can make enchiladas in any quanttity–but if you’re going to the trouble, you might as well make a lot of them. [g] (They freeze well, though the tortillas will degrade when frozen and give you enchilada casserole, rather than discrete enchiladas.)

As a rule of thumb, a pound of cheese and twelve tortillas will make about a dozen enchiladas; sauce for a dozen enchiladas takes about one to one-a-and-a-half cans of El Pato, and three-four Tablespoons of olive oil. I almost always use three cans of El Pato, and end up with 2 1/2 – 3 dozen enchiladas.

All right. For starters, mince four or five (or six) cloves of garlic finely. Cover the bottom of a heavy saucepan with olive oil (about 1/8″ deep) and saute the garlic in the oil (the bits of garlic should just about cover the bottom of the pan, thinly). Cook until the garlic turns BROWN, but be careful not to burn it.

Turn heat down to low (or pull the pan off the burner temporarily) and add flour a little at a time to make a roux (paste about the consistency of library paste). Add the El Pato (or plain tomato sauce) and stir into the roux. Add WATER, in an amount equal to the tomato sauce (I just fill up the El Pato cans with water and dump them in). Stir over low heat to mix, squishing out any lumps that may ocur. If you used plain tomato sauce, add chili to taste (or if you use El Pato and want it hotter, add extra chili)—roughly one large tablespoon of raw chile per can of tomato sauce.

Leave on very low heat, stirring occasionally, WHILE:

1) heating oil (I use canola oil, but you can use any vegetable oil, including soy, peanut, or olive) in a small, heavy frying pan. Heat over medium heat, and watch it as it gets hot; if it starts to smoke, it’s too hot–turn it down.

2) grating cheese

3) and chopping onion coarsely.

At this point, the sauce should have thickened slightly, and will cling to a spoon, dripping slowly off. Turn off the heat under the sauce, or reduce to low simmer. (If at any time, the sauce seems too thick, stir in a little more water.) Stir occasionally to prevent it sticking.

Now put out a clean dinner plate for assembling the enchiladas, and a baking dish to put the completed ones in.

With a pair of tongs, dip a fresh corn tortilla briefly (just long enough for the oil to sputter–2-3 seconds) into the hot oil. Let excess oil run off into the pan, then dip the now-flexible tortilla into the sauce, laying it back and forth with the tongs to coat both sides.

Lay the coated tortilla on the dinner plate (and put down the tongs [g]). Take a good handful of cheese and spread a thick line of it across the center of the tortilla (you’re aiming for a cylinder about two fingers thick). If you like onions in your enchiladas (I don’t, but Doug does, so I make half and half), sprinkle chopped onions lightly over the cheese. Roll the tortilla into a cylinder (fold one side over the cheese, then roll up the rest of the way, and put the enchilada in the baking dish. (They won’t have a lot of sauce on them at this point)).

When the baking dish is full, ladle additional sauce to cover the enchiladas thoroughly, and sprinkle additional cheese on top for decoration (I also sprinkle a few onions at one end of the baking dish, so I know which end is onion). Bake at 325 (F.) degrees for between 10-15 minutes–until cheese is thoroughly melted–you can see clear liquid from the melted cheese bubbling at the edge of the dish, and the enchiladas will look as though they’ve “fallen in” slightly, rather than being firmly rounded. Serve (with a spatula).

The method is the same for other kinds of enchiladas; you’d just make the filling (meat, seafood, etc.) as a separate step ahead of time, and use as you do cheese (for chicken enchiladas, brown diced chicken slowly in a little oil with minced garlic, onion, red and green bell pepper, and cilantro (coriander leaf)–bell pepper optional, and in very small quantity; for beef, you can use either ground beef or machaca).

It usually takes me a little more than an hour to do three dozen enchiladas, start to finish. Once the sauce is made, cheese grated, etc., though, the assembly is pretty fast.

Hope y’all enjoy them!

–Diana

Happy New Year – Top 8 of 2008

Top 8 of ’08

I had some difficulty coming up with a good list, largely because I like all kinds of things (dachshunds, murder mysteries, Audi SL6’s, hickory-smoked barbecue…), but not necessarily eight of any of them.

On the other hand, I do like to eat. And cook.

So here’s a list of my favorite eight recipes. As time allows over the next couple of weeks, I’ll actually post said recipes, but for now—I spent eight hours today driving to and from Indio, CA, to pick up my new dachshund puppy (name still up for grabs, though it might be Homer), and am consequently about to head for bed.

ENCHILADAS

ENCHILADAS

MACHACA

CURRY

CHICKEN WITH MUSHROOMS IN ORANGE SAUCE

DRUNK CHICKEN PASTA SALAD

BROWNIES

HOLIDAY FUDGE

GUACAMOLE WITH HOME-MADE CHIPS

Happy New Year!

-Diana

See my Recipes webpage for links to recipes and blogs where I’ve mentioned my favorite foods and recipes. <g>

This webpage was last updated on Tuesday, April 22, 2025 at 4:00 a.m. by me, Diana Gabaldon, or my Webmistress.

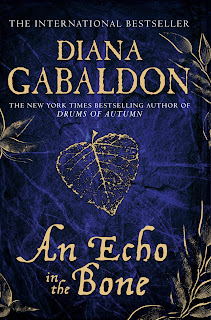

UK Cover Proof for ECHO

I just got the cover proof for the UK edition of AN ECHO IN THE BONE. As usual [g], this is Completely Different from the US design–but also different from the most recent UK versions of the series cover, because we have a new UK publisher for ECHO–Orion.

The cover is really striking, and I like it (slight quibble with the typography and balance of the title, but art departments routinely mess with those things; this isn’t a finished product, by any means).

Anyway, I asked the editor whether Orion would mind my showing it to you–since y’all were so interested and helpful in the question of the new US cover–and he said that would be great; he’d be very interested to hear your comments.

Only difficulty being that I don’t know whether I can insert a .jpg into this blog–or if so, how. Do any of y’all have any good technical advice? (If I can’t post it here, I’ll put it up on my website, but that takes a bit longer.)

Thanks!

OK, I _think_ I’ve got it. Let’s see now…OK! I think it worked.

Really striking, as I say–the gradations of blue are gorgeous; don’t know how well they’ll show up here. And the leaf in the center is–they tell me–going to be embossed in gold foil, so will be much more visible. (I was impressed that somebody thought about it enough to come up with the skeletal leaf as a non-bony [g] metaphor for the title.)

Anyway, let me know what you think!

Thanksgiving: Gravy, Graves, and Sex-Drunk Hoot-Owls

My apologies for taking so long to get my Thanksgiving wishes up for you. Thanksgiving was delightful, but busy—the Most-Eaten dishes (the ones everyone gobbles and raves over—it’s different every time) this time were a new one, mushroom pate’ surrounded by sliced pears sprinkled with gorgonzola crumbles and walnuts and drizzled with balsamic vinaigrette (served with fresh French bread)—and the always popular standby, deviled eggs. [g]

I did the usual fruit-stuffed turkey (a couple of nice people had seen me mention this and asked for the recipe—I don’t think you could actually dignify it by calling it a “recipe”; I literally stuff the turkey with fruit (and onions and garlic and baby carrots—but mostly whatever’s in the fruit bowl; this year it was apples, oranges, and grapes, and I forgot to buy baby carrots). I don’t like bready stuffing or dressing, and since I’m cooking, I get to eat what I like (the main reason for cooking, if you ask me)), but since I was lacking carrots and used oranges (which I usually don’t), the bird was even juicier than usual—the benefit of this particular stuffing method is that you never have a dry turkey, and the subsequent gravy is wonderful; light and very flavorful (now I do sort of have a gravy recipe, which I’ll post on the website, along with a Thanksgiving excerpt from AN ECHO IN THE BONE—www.dianagabaldon.com)—and consequently arrived on the platter in several pieces [cough].

Well, you’re just going to carve it up anyway…though I must here recount an anecdote my husband told me: his mother—a famously good cook, and justly proud of it—had guests one Thanksgiving, and Something Happened to the turkey, causing it to literally collapse. One of the guests viewed the wreckage on the platter, laughed, and said, “Kay, that bird looks like somebody shot it out of the sky with a howitzer!” My mother-in-law—also famously red-headed, and with a famous temper to match—replied, “If you think you can do it better, you son-of-a-b!tch, fix it yourself! Get out of my house!” (My husband says the guest didn’t leave, but apologized, and a nice meal was eventually had by all.)

So a lovely time was had by all here, too, followed by a pleasantly langourous evening. Friday I arose refreshed, and—not being reckless enough to go anywhere near a shopping mall on Black Friday—spent the whole day working on manuscripts: writing another 2000 words of AN ECHO IN THE BONE, and copy-editing for my son, who’s just finishing up the final stages of his first novel (yes, if and when it gets published, I’ll tell you all about it). Followed by a late-night turkey sandwich on whole-wheat bread with sliced pears, walnuts and gorgonzola (and a little mayonnaise to keep the walnuts from falling out), with a glass of white wine—the best part of a Thanksgiving weekend.

Fine. So yesterday, I had it in mind to answer email, finish writing an update for the website, choose an excerpt to post, and possibly begin the Christmas cards (no, don’t write to tell me to skip the Christmas cards so I can finish the book; I only send cards to distant relatives, close friends, editors, and agents, and I can manage twenty Christmas cards without slowing my progress appreciably). The universe had other plans.

Yesterday has to have been one of the more surreal days in a life that’s contained quite a few. As I was brushing my teeth, my husband came in and suggested that as the weather was nice (it had rained for the preceding three days), we might drive down to Tucson, and visit the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, since we hadn’t been there for ages. (This is a wonderful outdoor live “museum,” featuring the animals, ethnography, geology, and botany of the Sonoran and Anza-Borrego Desert. We’ve been members for years, and usually get down there every three or four months. If any of you who live in the area or pass through are interested, here is their website.)

I thought this was a terrific idea. The email and Christmas cards could certainly wait, and if I took a wodge of Sam’s manuscript to proof-read in the car, I’d still end up with my evening work hours free and clear to work on ECHO, so why not? (Besides, when you’re a writer, you have to prioritize, in order to get the important things done. My personal priorities are 1) family, 2) book, 3) exercise, and 4) garden. You’ll notice that “housework,” “TV watching,” and “taking part in casting discussions” aren’t on that list. Going to the ASDM with Doug definitely falls under #1 there, and also neatly takes care of #3, as circumnavigating the whole place is easily a three or four-mile walk.)

So away we went, and had a wonderful time. The weather was ideal—about 68 degrees, clear and bright—and all the animals were out. The animal residents of the Museum are mostly in natural-habitat (very large) enclosures, which means that it’s just about as easy to spot them in there as it would be in their natural habitats. We normally manage to see about 2/3 of them, but seldom spot the wild turkeys, the deer, or the coyotes.

We’d been batting a thousand, though, approaching the coyote habitat (which is a huge enclosure liberally studded with rocks, mesquite, cactus and….well, they essentially just put up invisible mesh around a quarter-acre of desert); we’d seen mountain lion, bobcats (gato montes; all the legends and signs are bilingual, and it’s very entertaining to back-translate the Spanish names, on occasion. “Cat of the mountains,” it means), porcupine, gray fox, wolves (curled up asleep, but still, we saw them), and the turkey (very gorgeous in the sunlight, with his red head and blue and green iridescent feathers—a far cry from the overbred white creatures who end up on Thanksgiving platters—and remind me sometime to tell you the story of my husband, my father-in-law, the cattle round-up, and the ten thousand white turkeys…), and the deer.

So we were making bets on our chances of seeing a coyote—remarking as we did so that in fact, our chances of seeing a coyote were a lot better at home than they were at the ASDM. We live right in the middle of Scottsdale, but coyotes routinely roam our neighborhood; one day we were driving down our street and saw an enormous coyote sitting at the bus stop on the corner, completely nonchalant. I often see them crossing streets in broad daylight, and last New Year’s Day, found myself following one up the street—this is a completely urban part of town, mind—while out for a walk, and often hear them carrying on at night. (Coyotes do not actually “howl,” btw. Wolves howl. Coyotes gibber, wail, and laugh like maniacs. That’s not a figure of speech, either; they laugh like maniacs, and it’s one eerie thing to listen to in the dead of night, which is when I usually hear them.)

Well, it was a day in a thousand—we saw not one, but two coyotes, trotting up and down about their business. We also saw the beaver (who was awake, for once), the river otter, prairie dogs, chipmunks, a herd of javelina, and more snakes than you could shake a stick at. (To say nothing of all the cool geology and mineral exhibits, but you can pretty much count on the spectacular chunks of wulfenite, azurite, and malachite still being where you saw them last, waiting patiently to be admired again.)

Rolled home, accompanied by Doug, a Dove ice-cream bar, and a large chunk of son’s manuscript (good book, I’m pleased to report). It’s nearly winter, and the days are drawing in; it’s getting dark by 5:30, which is when we arrived home, and the Great Horned owls were At It already. (Late November/early December is their courting season, and they’re hooting to and fro in ecstasy all night long. One of them was sitting in a tall palm tree right next to our house—and if you don’t think seeing a Great Horned owl in a palm tree is a slightly surreal experience…)

My first act on returning home, when Sam is visiting, is to greet his dogs (the Little Bad Dogs, aka Charlie the corgi and Otis the pug) and march them directly out back to go potty, as they’re very unreliable about this duty if not sternly supervised, dog-door notwithstanding.

We stepped out through the back door of the garage—and they immediately shot for the Back Forty (as we refer to the wild half-acre that forms the back half of our property; there are a couple of horse corrals with a ramada back there, and a tackroom (no, no horses at present; there have been and likely will be again at some point, but none now), but otherwise nothing but eucalyptus trees (the owls adore these), mesquite, palo verde and vast expanses of tumble-weed), barking. I looked to see what they were barking at, didn’t spot anything (no surprise), and paused to have a quick look at the garden and draw up a mental chore list for Sunday afternoon (prime gardening time): prune back grapevines, finish harvesting pomegranates (we had a plague of woodpeckers this year, so the crop is much reduced), rip out wads of mint, trim and fertilize the roses…emerging from the garden, I saw that Otis and Charlie were still out back; I could see them under the big eucalyptus, sniffing around.

OK, slight digression here. We had to put down our oldest dog (Really Old. I estimated that in dog years, she was 112. We’d been checking her every morning for the last year, to see if she was still breathing. She was, but having an increasingly hard time of it, poor old thing), Molly, about ten days ago. We bury all the dogs under the big eucalyptus out back, and had planted Molly with due ceremony next to her old pal, Ajax.

It’s not unusual for dogs to go smell and scratch at the grave of a recently deceased acquaintance—this behavior usually followed by ceremonially peeing on the gravesite—so I thought that’s what Otis and Charlie were about, and strolled out to join them, thinking to pay my respects and put a rose on the grave (the roses do very well this time of year, since it’s finally cool enough that the fresh blossoms don’t fry on emergence).

Now, it was getting dark, and a good thing, too. For a minute or two, I had no idea what I was looking at. Then I knew what I was looking at, but no idea why I was looking at it. Somebody had shoveled most of the dirt out of Molly’s grave, revealing the neat rectangle Doug had made for her—and there was something blobbish, dark, wet and nasty-looking in it. A second later, I realized that the wet-and-nasty was what was left of Molly—this realization aided by the presence of wads of wiry gray hair all over the place (Molly went to the vet’s once, and the vet’s assistant, passing the door of the exam room, paused and said sympathetically, “Oh—a bad hair day every day, huh?”). The dogs and I were nonplused.

Went and summoned Doug and Sam, with shovels, and we held a hasty reprise of the funeral, this one much less ceremonious, ending in the placement of a chunk of old swimming pool fence over the site to prevent further desecration. Our best guess was that coyotes had dug up and half-devoured the remains—which was rather a sobering thought, as the entire yard is surrounded by a six-foot concrete block and stucco wall. I knew coyotes could jump, but…

Well, no one in the family is what you’d call squeamish, so we repaired inside for a post-Thanksgiving supper of pancakes and turkey with butter and maple syrup (pancakes being Doug’s piece de resistance, and very tasty they are, too). Tidied up, read a bit while Doug watched football, tucked him in, and prepared to go lie down for a quick evening nap before starting work. Took Otis and Charlie out for a potty-break.

Once again, they shot for the Back Forty, barking their heads off. Followed them at a dead run (in my red flannel pajamas and Uggs, mini-flashlight in hand). Luckily, there was nothing in the yard—but there was what sounded like a sizable pack of coyotes directly on the other side of the back wall (there’s a narrow service alley back there, between us and the neighbors on that side), yipping, gibbering and laughing their heads off. Not what you want to hear at 10 o’clock of a dark night, with sex-drunk owls hooting to and fro overhead, a desecrated grave full of ghastly remains at your feet, a pug Who Knows No Fear (Otis being certifiably insane; he’s the sort who loves to hop up and down, frothing at the mouth and calling big dogs bad names in public, secure in the knowledge that he’s on a leash) shrieking abuse at them from close range, a corgi also shaped like a coyote snack also barking, but from a slightly more prudent distance (Charlie’s bred for a cow-dog and thus possessed of common sense)—and the certain knowledge that those gibbering maniacs can indeed get over that wall if they want to.

After a certain amount of yelling and flashlight brandishing—and running down Otis the Fathead and snaffling him by the collar—we repaired inside, locked the panel over the dog-door (hey, if they’re going to come pillage the family cemetery, what’s to stop them coming right on in after the dog food?), lay down, and passed out. Temporarily.

The phone rings, waking me out of a sound sleep, so I’m more than slightly confused to hear my younger daughter telling me that her friend (visiting from New York) is in terrible pain, and they think she needs to go to the hospital, but she (the friend) won’t go without me. (Longtime childhood friend of Jenny’s, deplorably estranged from her parents for years. I’m sort of a surrogate mother.)

Shaking my head in hopes of clearing my wits enough to drive, I go wake Doug to tell him where I’m going and assure him that he doesn’t need to come with me, get dressed, stuff a cold-pak from the freezer and a bottle of ibuprofen into my purse, and go—pausing on my way out to grab the folder containing Sam’s manuscript (I’ve been in emergency rooms before. No matter what the situation, you’re probably going to want something to read).

Arrive to find the poor girl writhing in pain, unable to find a comfortable position that will ease it, terrible pain from the middle of her back down her right arm, pins-and-needles…Jenny and another friend had taken her to an urgent care facility earlier in the day, where they diagnosed the problem as muscle spasm/possible pinched nerve, and prescribed her a painkiller. Painkiller is obviously not working, and now it’s 11 PM. Tried a little trigger-point massage, just in case—it helped slightly, but pain resumed full-force as soon as I stopped, and when we asked if she thought she needed to go to the emergency room, she said she did.

So the four of us—C. (the injured friend) lying on a seat, writhing and emitting small, pitiful cries, Jenny, self, and other friend taking it in turns to rub her neck or her arm or chafe her hands for distraction—spent an hour in the lobby (luckily, it wasn’t a busy night), chatting and making remarks under our breaths about the other people in the waiting room, who were the usual motley crew one sees in an emergency room on a Saturday night, including a young man who looked as though he’d been living in a dumpster with an ice-bag on his head (that is, he had the ice-bag on his head in the waiting room, not in the dumpster), accompanied by his much spiffier girl-friend, a buxom specimen with drug-googly eyes and a large coat on which was painted in big red and green letters, “Kill the Brain and the Whole Ghoul Dies”. Not that we looked that great, all things considered, but still.

Four hours later, staggered (literally; C. had been given Valium, a shot of muscle relaxant and some Very Potent painkiller—sufficiently potent that she couldn’t keep it down, and barfed twice getting from the emergency room to the car—a distance of about a hundred feet) out of the hospital, drove the girls to Jenny’s place, and made my way home—just in time to take Otis and Charlie out again. This time, I took them into the inner yard, and they accomplished their business at 4 AM by the peaceful glow of Christmas lights, the night now silent save for the soft Hoo! Hoo-hoo! (male owls hoot once, females twice) of love in the trees.

And I hope all y’all had a lovely weekend, too! [g]

.jpg)