Here are some brief video clips from the live launch of “Outlander: The Musical” in Aberdeen last month!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i37mvexRYUk

(Apologies for the poor sound; these were done with a small hand-held camera.)

Here are some brief video clips from the live launch of “Outlander: The Musical” in Aberdeen last month!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i37mvexRYUk

(Apologies for the poor sound; these were done with a small hand-held camera.)

IT’S GONNA BE A BUSY WEEKEND!!

I’ll be appearing at the Decatur Book Festival and Dragon*Con in Atlanta this weekend—pretty much simultaneously! Events and times are listed below (please note that I won’t be doing the events scheduled for Monday!).

Now, normally, I don’t Twitter [g]–no time!–but it strikes me that this weekend might just be the kind of situation where that might be helpful. So—just in case y’all want to follow me temporarily, my Twitter ID is “Writer_DG.”

DECATUR BOOK FESTIVAL

All my events in Decatur will be on Saturday afternoon (Sept. 4):

1:00 PM – “Meet and Greet” in the AJC tent. This is a brief opportunity to chat with readers. It’s not a book-signing.

3:00 PM – main talk/reading – Presbyterian Church. I’ll talk about anything y’all would like to hear about

(The talk will be followed by a book-signing—usually held across the street. !!!I will have a limited number of Outlander: The Musical” CD’s!!! available at this signing. (limited by the number I can carry…))

5:00 PM – Panel. “Break in Case of Emergency: This Book Could Save Your Life!” on The Escape teen stage. (Advice from adult authors on books to read.)

DRAGON*CON

***An Hour with Diana Gabaldon

D. Gabaldon; Mon 10:00 am; Intl. C

[W]

Outlander in Graphic Terms

Diana and Betsy discuss how the graphic

version came to be and the transition

from prose to graphic novel. D. Gabaldon,

B. Mitchell; Fri 5:30 pm; Fairlie [H]

(We’ll be showing off some of the art–and will have an Actual Book to show, too!)

Sexy Science Fiction

What makes a book sexy? Naked women

and actual sex scenes? Or are there other

literary pheromones at work? J. Ward,

G. Martin, D. Gabaldon, D. Whiteside, G

Mitchell (M); Fri 10:00 pm; Fairlie [H]

Trends in Paranormal/Urban Fantasy

Fiction

This panel will discuss the very fluid

paranormal/urban fantasy fiction market.

C. Burke, C. L. Wilson, J. St. Giles, D.

Gabaldon, L. Gresh, D. Knight; Fri 11:30

am; Manila/Singapore/Hong Kong [H]

Pros Discuss Plot Development

These pros discuss methods of developing

unpredictable, but believable plots. C.

Burke, J. Moore, J. Sherman, J. Maberry,

D. Gabaldon, L. Gresh; Sat 8:30 pm;

Manila/Singapore/Hong Kong [H]

Ingredients for great fiction

A little sugar, a little spice? A surprising

plot, a great cast of characters, intriguing

settings blend into great fiction. N.

Knight, G. Watkins, J. Wurts, A. Sowards,

M. Resnick, C. Eddy, S. M. Stirling,

D. Gabaldon; Sun 5:30 pm; Manila/

Singapore/Hong Kong [H]

***Roundtable

Got a question? This is a question and

answer panel that will address questions

from the audience. S. Chastain, D.

Dixon, J. Moore, C. Douglas, J. St. Giles,

D. Gabaldon; Mon 1:00 pm; Manila/

Singapore/Hong Kong [H]

***The Future of Fantastic Fiction

This panel explores markets with wellestablished

authors making suggestions

for audience members. G. Hayes, A.

Martin, E. Moon, J. St. Giles, D. Gabaldon;

Mon 4:00 pm; Manila/Singapore/Hong

Kong [H]

*** I’m sorry to miss these events—especially the “Hour with Diana”!—but the unfortunate fact is that the DragonCon programming committee didn’t bother to send me this schedule. I got it from a fan who’d picked it up from the website three days ago—by which time I (rather naturally) had already booked my flights, leaving Monday morning. Will hope to catch up with y’all at one of the other events over the weekend, though!

Why, yes, actually I _have_ (in and amongst everything else) been working on Book Eight. [g] I think I showed you a brief snip of the pickup to the Jem-in-the-tunnel cliffhanger last month; here’s a likewise brief snip of the one between Jamie and Lord John:

Excerpt, Book Eight

Copyright 2010 Diana Gabaldon

He’d been quite resigned to dying. Had expected it from the moment that he’d blurted out, “I have had carnal knowledge of your wife.” The only question in his mind had been whether Fraser would shoot him, stab him, or eviscerate him with his bare hands.

To have the injured husband regard him calmly, and say merely, “Oh? Why?” was not merely unexpected, but…infamous. Absolutely infamous.

“Why?” John Grey repeated, incredulous. “Did you say ‘Why’?”

“I did. And I should appreciate an answer.”

Now that Grey had both eyes open, he could see that Fraser’s outward calm was not quite so impervious as he’d first supposed. There was a pulse beating in Fraser’s temple, and he’d shifted his weight a little, like a man might do in the vicinity of a tavern brawl, not quite ready to commit violence, but readying himself to meet it. Perversely, Grey found this sight steadying.

“What do you bloody mean, ‘why’?” he said, suddenly irritated. “And why aren’t you fucking dead?”

“I often wonder that myself,” Fraser replied politely. “I take it ye thought I was?”

“Yes, and so did your wife! Do you have the faintest idea what the knowledge of your death _did_ to her?”

The dark blue eyes narrowed just a trifle.

“Are ye implying that the news of my death deranged her to such an extent that she lost her reason and took ye to her bed by force? Because,” he went on, neatly cutting off Grey’s heated reply, “unless I’ve been seriously misled regarding your own nature, it would take substantial force to compel ye to any such action. Or am I wrong?”

The eyes stayed narrow. Grey stared back at them. Then he closed his eyes briefly and rubbed both hands hard over his face, like a man waking from nightmare. He dropped his hands and opened his eyes again.

“You are not misled,” he said, through clenched teeth. “And you _are_ wrong.”

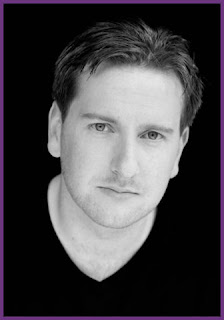

Well, having embarrassed the heck out of Mr. Scott-Douglas, [cough] allow me now to introduce you to Mr. Kevin Walsh!

(I showed this picture to our excellent web-mistress, who said, “Does every Scot have a kilt pic? What they don’t realize is, all they have to do is go on any Diana Gabaldon fan board, and pick up any single woman they want, from anywhere in the world! *g* Doesn’t even matter what they look like, they just need the kilt and the accent.” )

Kevin is both the singer and the song. By which I mean that he’s the composer and creator of all the music for the Outlander: The Musical CD—and also sings the voices of Dougal MacKenzie and Ian Murray _on_ the CD. (You can hear him as Dougal in “The Message” and as Ian in the hilarious “Why Did I Marry a Fraser?” (in which Jamie and Jenny bicker in the background as Ian and Claire condole with each other: Ian/Claire: “[Frasers]…they’re awkward/and sulky/bad-tempered/and vain” (Jamie: “VAIN?!” Claire: “Yes, you strut about there like a Highland John Wayne…”)) as well as a brief bit in “I Am Ready”).

Kevin’s also aka the Laird of Balnamoon – pronounced, he says, “Bonny Moon” in old Scots—this being the name of his house, “Cotton of Balnamoon,” an ancient structure once belonging to a Jacobite laird named James Carnegy-Arbuthnott*)

* James Carnegy-Arbuthnott, Laird of Balnamoon, favoured the Jacobite cause and was known as the Rebel Laird. He was Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s Deputy-Lieutenant of Forfarshire and an officer in Lord Ogilvy’s Angus regiment. He survived the Battle of Culloden in 1746 and fled to Glen Esk where he was harboured by locals until he was betrayed by the local Presbyterian minister. Sent for trial in London, he was acquitted on a misnomer. (In 1745 he had added his wife’s surname and territorial designation of Arbuthnott of Findowrie to his own name, from whence arose the confusion). [From Wikipedia]

Pictures, you say. Well….see, the thing is, if I’m taking pictures, I’m always looking around for something to take a picture _of_. Which is not an unreasonable thing to do, but it stops me actually _seeing_ things.

And it gets in the way of the things that are looking for me.

For instance, the last bit of the recent trip was two and a half days in Ireland. This was research, as part of SCOTTISH PRISONER takes place there—but rather random research, as I wasn’t looking for a specific battlefield or anything of that sort, but just absorbing the vibes of County Galway and Limerick (as well as Dublin) and sitting around in pubs listening to people talk (I have some slight ear for Scots, but none at all for Irish regional accents or idiom).

Well, so. Our path to Limerick took us (by plan) through Athlone, as a certain amount of 17th-century Jacobite plotting went on there, and I thought it might be useful. Nothing specific in mind, though, so we were just driving through the city, looking round in a vague way for the castle. “You don’t know where it is?” asked my husband (gallantly doing all the wrong-side-of-the-road driving, and thus slightly white-knuckled in the narrow streets).

“Nope,” I said cheerily. “I may not even need it, but if I do, I’m sure we’ll find it.” So on we went, reaching the far side of the city pretty fast (it’s a small city, Athlone). Rather than get onto an unfamiliar motorway, we pulled into the parking lot of a shopping center—which was across the street from a park, with a river running through it.

OK. One of my basic principles when on foreign ground is that you always head for water. River, lake, ocean, pond—it doesn’t matter. Something interesting is always going on near water. So we crossed the road, and Doug headed—with logic—right for the river. I stopped dead, at a ratty little poster in a frame, showing faded depictions of the flora and fauna to be found on the River Shannon (that being what we standing next to). I took a quick, but intense look at this, and when I spotted “amphibious bistort,” I heard, clear as anything, the following:

“Fraser glowered at the plant in his hand.

“And what’s that?”

“An amphibious bistort, if I’m not mistaken,” Grey replied, with some pleasure at the name.

“Can ye eat it?”

Grey surveyed the spindly thing critically and shook his head.

“Not unless you were starving.”

“I’m not. Put it back and let’s go.”

Right. So the River Shannon and the amphibious bistort were looking for me—but I certainly wouldn’t have found them, if I’d been looking for church spires or cud-chewing cows to take photos of. (No, I have no idea why these people are where they are; I just know they _are_, because I’ve just seen them there.) And on the way back through town, sure enough, Castle Athlone materialized right in front of us, and I spent a blissful twenty minutes climbing through it. So when the time comes, I can pull that memory up entire, from the tiny flowering plants growing in the cracks of the black stone, to the way the arrow slits widen on the inner aspect, to allow for someone drawing a bow—and I know that a bow-shot from one of those slits would have reached a boat coming ashore from the Shannon (having come down from Lough Rea—don’t ask me who’s in the boat or who’s shooting at them; I don’t know that yet), because I know how far it is from the Castle to the River—not far at all.

And that’s why I don’t take pictures when I travel. (I _do_ collect postcards from art museums.)

So I’m afraid the only picture I came home from Scotland with is the one above, of me and Big Bir—er, me and Mr. Allan Scott-Douglas (the voice of Jamie Fraser on the outlanderthemusical CD), who very graciously came to have a drink with me and sign a bunch of CD’s. (NO, I have _not_ just made some scandalous remark that caused Mr. Scott-Douglas to blush—would I do that? He’s just got a ferocious sunburn from outdoor rehearsals for his next show, “King Arthur”, which is being performed at Craigcrook Castle near Edinburgh, later this month. See here for details.)

[As an afterthought, it seemed only fair to show you a photo of Allan _in_ character, though he's no less charming as himself.]

Oh—before I forget, there’s a brand-new video of the song-snips from Outlander: The Musical, here! (And many, many thanks to the talented Michelle Moore, who made it!)

Not that I have been _entirely_ frivolous over the last couple of weeks. I’ve also just finished a novella titled “Lord John and the Plague of Zombies,” and here’s a bit of it, for your entertainment–hope you enjoy it!

“Lord John and the Plague of Zombies” – excerpt

Copyright 2010 Diana Gabaldon

[This will be published in an anthology titled DOWN THESE STRANGE STREETS, edited by George R.R. Martin and Gardner Dozois. No, I don’t have a pub date for this yet, but am assuming sometime in 2011.]

“Your servant, sah,” he said to Grey, bowing respectfully. “The Governor’s compliments, and dinner will be served in ten minutes. May I see you to the dining room?”

“You may,” Grey said, reaching hastily for his coat. He didn’t doubt that he could find the dining-room unassisted, but the chance to watch this young man walk…

“You may,” Tom Byrd corrected, entering with his hands full of grooming implements, “once I’ve put his lordship’s hair to rights.” He fixed Grey with a minatory eye. “You’re not a-going in to dinner like that, me lord, and don’t you think it. You sit down there.” He pointed sternly to a stool, and Lieutenant-Colonel Grey, commander of His Majesty’s forces in Jamaica, meekly obeyed the dictates of his nineteen-year-old valet. He didn’t always allow Tom free rein, but in the current circumstance, was just as pleased to have an excuse to sit still in the company of the young black servant.

Tom laid out all his implements neatly on the dressing-table, from a pair of silver hairbrushes to a box of powder and a pair of curling tongs, with the care and attention of a surgeon arraying his knives and saws. Selecting a hairbrush, he leaned closer, peering at Grey’s head, then gasped. “Me lord! Tthere’s a big huge spider–walking right up your temple!”

Grey smacked his temple by reflex, and the spider in question—a clearly visible brown thing nearly a half-inch long—shot off into the air, striking the looking-glass with an audible tap before dropping to the surface of the dressing-table and racing for its life.

Tom and the black servant uttered identical cries of horror and lunged for the creature, colliding in front of the dressing table and falling over in a thrashing heap. Grey, strangling an almost irresistible urge to laugh, stepped over them and dispatched the fleeing spider neatly with the back of his other hairbrush.

He pulled Tom to his feet and dusted him off, allowing the black servant to scramble up by himself. He brushed off all apologies as well, but asked whether the spider had been a deadly one?

“Oh, yes, sah,” the servant assured him fervently. “Should one of those bite you, sah, you would suffer excruciating pain at once. The flesh around the wound would putrefy, you would commence to be fevered within an hour, and in all likelihood, you would not live until dawn.”

“Oh, I see,” Grey said mildly, his flesh creeping briskly. “Well, then. Perhaps you would not mind looking about the room while Tom is at his work? In case such spiders go about in company?”

Grey sat and let Tom brush and plait his hair, watching the young man as he assiduously searched under the bed and dressing-table, pulled out Grey’s trunk, and pulled up the trailing curtains and shook them.

“What is your name?” he asked the young man, noting that Tom’s fingers were trembling badly, and hoping to distract him from thoughts of the hostile wildlife with which Jamaica undoubtedly teemed. Tom was fearless in the streets of London, and perfectly willing to face down ferocious dogs or foaming horses. Spiders, though, were quite another matter.

“Rodrigo, sah,” said the young man, pausing in his curtain-shaking to bow. “Your servant, sah.”

He seemed quite at ease in company, and conversed with them about the town, the weather—he confidently predicted rain in the evening, at about ten o’clock–leading Grey to think that he had likely been employed as a servant in good families for some time. Was the man a slave? he wondered, or a free black?

His admiration for Rodrigo was, he assured himself, the same that he might have for a marvelous piece of sculpture, an elegant painting. And one of his friends did in fact possess a collection of Greek amphorae decorated with scenes that gave him quite the same sort of feeling. He shifted slightly in his seat, crossing his legs. He would be going into dinner soon. He resolved to think of large, hairy spiders, and was making some progress with this subject when something huge and black dropped down the chimney and rushed out of the disused hearth.

All three men shouted and leapt to their feet, stamping madly. This time it was Rodrigo who felled the intruder, crushing it under one sturdy shoe.

“What the devil was that?” Grey asked, bending over to peer at the thing, which was a good three inches long, gleamingly black, and roughly ovoid, with ghastly long, twitching antennae.

“Only a cockroach, sah,” Rodrigo assured him, wiping a hand across a sweating ebon brow. “They will not harm you, but they are most disagreeable. If they come into your bed, they feed upon your eyebrows.”

Tom uttered a small strangled cry. The cockroach, far from being destroyed, had merely been inconvenienced by Rodrigo’s shoe. It now extended thorny legs, heaved itself up and was proceeding about its business, though at a somewhat slower pace. Grey, the hairs prickling on his arms, seized the ash-shovel from among the fireplace implements and scooping up the insect on its blade, jerked open the door and flung the nasty creature as far as he could—which, given his state of mind, was some considerable distance.

Tom was pale as custard when Grey came back in, but picked up his employer’s coat with trembling hands. He dropped it, though, and with a mumbled apology, bent to pick it up again, only to utter a strangled shriek, drop it again, and run backwards, slamming so hard against the wall that Grey heard a crack of laths and plaster.

“What the devil?” He bent, reaching gingerly for the fallen coat.

“Don’t touch it, me lord!” Tom cried, but Grey had seen what the trouble was; a tiny yellow snake slithered out of the blue-velvet folds, head moving to and fro in slow curiosity.

“Well, hallo, there.” He reached out a hand, and as before, the little snake tasted his skin with a flickering tongue, then wove its way up into the palm of his hand. He stood up, cradling it carefully.

Tom and Rodrigo were standing like men turned to stone, staring at him.

“It’s quite harmless,” he assured them. “At least I think so. It must have fallen into my pocket earlier.”

Rodrigo was regaining a little of his nerve. He came forward and looked at the snake, but declined an offer to touch it, putting both hands firmly behind his back.

“That snake likes you, sah,” he said, glancing curiously from the snake to Grey’s face, as though trying to distinguish a reason for such odd particularity.

“Possibly.” The snake had made its way upward and was now wrapped round two of Grey’s fingers, squeezing with remarkable strength. “On the other hand, I believe he may be attempting to kill and eat me. Do you know what his natural food might be?”

Rodrigo laughed at that, displaying very beautiful white teeth, and Grey had such a vision of those teeth, those soft mulberry lips, applied to—he coughed, hard, and looked away.

“He would eat anything that did not try to eat him first, sah,” Rodrigo assured him. “It was probably the sound of the cockroach that made him come out. He would hunt those.”

“What a very admirable sort of snake. Could we find him something to eat, do you think? To encourage him to stay, I mean.”

Tom’s face suggested strongly that if the snake was staying, he was not. On the other hand….he glanced toward the door, whence the cockroach had made its exit, and shuddered. With great reluctance, he reached into his pocket and extracted a rather squashed bread-roll, containing ham and pickle.

This object being placed on the floor before it, the snake inspected it gingerly, ignored bread and pickle, but twining itself carefully about a chunk of ham, squeezed it fiercely into limp submission, then, opening its jaw to an amazing extent, engulfed its prey, to general cheers. Even Tom clapped his hands, and—if not ecstatic at Grey’s suggestion that the snake might be accommodated in the dark space beneath the bed for the sake of preserving Grey’s eyebrows, uttered no objections to this plan, either. The snake being ceremoniously installed and left to digest its meal, Grey was about to ask Rodrigo further questions regarding the natural fauna of the island, but was forestalled by the faint sound of a distant gong.

“Dinner!” he exclaimed, reaching for his now snakeless coat.

“Me lord! Your hair’s not even powdered!” He refused to wear a wig, to Tom’s ongoing dismay, but was obliged in the present instance to submit to powder. This toiletry accomplished in haste, he shrugged into his coat and fled, before Tom could suggest any further refinements to his appearance.

###

I’m actually a trifle disappointed. I have a nice official-looking card, signed by my surgeon, informing the world that I have a knee replacement, to be presented to the TSA as needed—and I didn’t need it! Apparently my new knee doesn’t contain enough metal (or not the right kind of metal) to set off most metal detectors in airports. Not that this is a ¬_bad_ thing, mind you…I was just all prepared to have sirens go off and then…nada. Quite the let-down!

On the other hand, if you’re going to spend 21 hours (count ‘em, 21! That’s just about One Whole Day _and_ Night!) getting home from Scotland, having been routed from Edinburgh to Paris to Minneapolis to Phoenix, anything that makes the passage through airports even minimally less complicated is welcome.

(I now have a new unfavorite airport. Granted, Charles DeGaulle is not _quite_ as horrible as JFK—where all the worst experiences of my long traveling life have taken place—but only because it’s newer and the people are somewhat more polite (no, really) while doing irrational things (after sending us through _two_ levels of security, including a hand-search of our cabin luggage, they sent us down a ramp to the gate. Only there wasn’t a plane at the end of it; we debouched into the street _outside_ the terminal, where we were obliged to wait fifteen minutes for a bus–whose driver then got LOST on the way to the plane (not kidding; he circled the terminal three times and kept making U-turns, dodging sewage-pumping trucks and construction equipment as we got closer and closer to flight time). It’s fortunate that among the few French things I know how to say is, “C’est mon mari!” (“That’s my husband!”), because otherwise, I would have lost Doug in CDG for sure…)

But we’re HOME, which is wonderful—the dachshunds were ecstatic at our reappearance and went in for exaggerated writhings of welcome, flinging themselves on the floor at my feet and peeing on the floor in demonstration of their delight–and we had an absolutely great time, zipping (in a leisurely fashion) from Edinburgh to Inverness to London to Ireland and back to Edinburgh.

We arrived in Edinburgh during the Fringe Festival, and left it on the first weekend of the regular Edinburgh Festival—both times, staying at The Scotsman, a delightful (if really eccentric—it used to be the office building for “The Scotsman” newspaper, and rather than gut the building, they just sort of…fitted…bedrooms into it, resulting in some truly peculiar rooms) place on the North Bridge, just off the Royal Mile.

Which I mention only because the Royal Mile in Festival time is something to see. There’s a great Scots word for that—“hoaching.” As in, “the place was hoaching with…” In this case, with hundreds of visitors fighting their way up and down the Royal Mile, or sprawling in tiny chairs outside restaurants with ice cream cones and pints of beer, or—like one family we saw, consisting of a father and four small boys—simply sitting on the pavement in a row, legs outstretched among the throng, placidly eating chips and vinegar out of cardboard trugs.

The Edinburgh Festival is a great cultural extravaganza: plays, musical performances, art exhibitions, literary readings, the Military Tattoo… “Fringe” is the Fringe Festival; a period before the regular Festival, featuring everything anybody wants to do and can find a place to do it in. The whole town becomes a warren of numbered “venues” (ranging from regular theaters to disused toilets), and street performers (you don’t see that many mimes and living statues anywhere else, even in Italy) and hawkers of Fringe performance tickets just about out-number the visitors. It’s the sort of experience that people call “colorful,” out of sheer inability to describe it more closely.

Now, I’ve performed myself a couple of times at the Edinburgh Literary Festival (a separately organized bookish part of the Festival season), but had never experienced “Fringe” before. As Doug observed, the people who benefit most economically during Fringe are the printers, who work day and night madly printing handbills, cards, brochures, posters, tickets, etc. for the constantly-changing array of performances—and the people (mostly young girls) who are hired to cruise through the crowds with litter-grabbers, picking all this stuff up off the street.

Naturally, some of what’s going on is great, and a lot of it is…well, it’s entertaining (or at least forces you to look at it, in the manner of traffic accidents). One heck of a lot of energy, though; the Royal Mile zaps and sparks like an electrical conduit, pretty much twenty-four hours a day. (Both Fringe and Festival occupy a lot more space than the Royal Mile, of course—but given limited time and the location of our hotel, we hung out mostly on the Mile and up in New Town.)

We were privileged to be invited to the dress rehearsal of one of the Fringe plays, a musical comedy translated from the Czech original, called “Desire.” Deeply entertaining, though I admit that attending in a mildly intoxicated state (believe me, the whole _town_ is mildly intoxicated during Fringe) probably helped.

Edinburgh wasn’t strictly for fun, though; while there, I met with Mike Gibb and Kevin Walsh, the creative team behind Outlander: The Musical, and we went together to confer with a couple of nice folk at the Scottish Department of Culture, regarding possibilities both for doing the showcase of songs at Tartan Day in New York next April, and for expanding to a full-scale stage production. A lot of encouragement, some useful suggestions—and Mike tells me he’s been sequestered at his hideout in Perthshire for the last two weeks, working feverishly on the complete libretto—can’t wait to see that!

In re knees, though, I will say that hauling up, down, and sideways over the steep terrain of Edinburgh did a lot for my rehab efforts. The next stop in Scotland did even more, that being a castle with a 99-step spiral staircase [g]—and a haunted room at the top. But it’s 4 AM here now, so Castle Stuart is a story for tomorrow!

Just a quick report from the Aberdeen front: The official “live” launch of OUTLANDER: The Musical took place yesterday, as part of the Aberdeen Tartan Day festivities, and a Really Good Time was had by all, or so I’m told. [g]

Here’s the Official Tartan Day Photo (as taken by the Official City of Aberdeen Photographer—meaning it’s in focus) of the scene in St. Nicholas’s Kirk. And here is the link to the slightly less official but very exciting photos taken by Shona Duthie during the performance. (The white-haired gentleman visible in one of these photos is Mike Gibb, the lyricist who wrote the songs.)

I’ve had lovely emails and enthusiastic messages from a number of people who were there, and Mike reports: “Great performances and amazing audience reaction. Quite a few American and Canadians in the audience who were ecstatic about the whole thing. We were basically full for all three performances with SRO at the first.”

I have family visiting, so we celebrated modestly with a bottle (or two) of wine, and I played the songs for the assembled company from my laptop, showing the pictures from Aberdeen. Spontaneous applause, much admiration for Allan’s socks [g] (not sure that the ladies viewing them realized that he’s wearing ghillies with wrapped garters, rather than having a truly eccentric Argyll pattern decorating his ankles—hard to see fine detail on a laptop screen (well, and there was Rather a Lot of wine, too…), and a general hope that he grows his hair out longer before the next appearance. Sue’s and Allan’s vocals hugely enjoyed, and general raising of glasses to Mike, Kevin, and all the performers (being not limited to the actual stage, I could play them the whole song-cycle. We waited until the young men in the party (aged 17 to 26) went off to their own devices before playing “Say the Words” (the duet between Jamie and Black Jack Randall in Wentworth), though.)

Anyway, congratulations to all involved with OUTLANDER: The Musical!

Anyone wanting to check out song samples, or order a CD of the complete song-cycle, can do so here.

And now I must go and start packing for Scotland! So I’ll be scarce online for the next couple of weeks—might manage one more post before I leave– but will hope to come back with nice pictures.

.jpg)

Or rather, Sue Robertson [g], who sings the role of Claire (and _very_ beautifully, too; she’s got a lovely warm, cut-crystal voice).

Sue Robertson (Claire)

Sue started on stage at the grand old age of 16 with Dundee Operatic Society (DOS) with whom she has played many principal roles over the years such as Nancy in ‘Oliver’, Minnie-Fay in ‘Show Boat’, Adelaide. in ‘Guys & Dolls’ and Millie in ‘Thoroughly Modern Millie’. Sue has also had the privilege of working alongside playwright Mike Gibb playing the part of Grace on four occasions during 2005 – 2007 in theatres across Scotland in his musical play ‘Five Pound & Twa Bairns’ and Barbara in ‘Sunday Morning on Dundee Law’ which Kevin Walsh wrote the music for. She has also been in the ‘The Steamie’ playing Doreen in 2002 and again in 2004. Sue has recently enjoyed playing the ‘mad’ role of Helen for the second time, working with the cast of ‘The Berries – Twa an’ a Half Pence a Pund’, written by her husband Dundee author, poet and playwright Gary Robertson.

.jpg)

Edinburgh born actor and singer, Allan Scott-Douglas has worked extensively in various musical and theatrical productions all over the UK since graduating with distinction from drama school in 2006.

In 2009, he had the distinct honour of being cast as ‘Scotland’s favourite son’, poet Robert Burns in ‘Ae Fond Kiss: The Life and Loves of Robert Burns’ for which he received critical acclaim. This included recording his first ever ‘Original Cast Recording CD’ which has been useful experience for his work on ‘Outlander – The Musical’.

He has also recently been involved in a modern day re-telling of the legend of King Arthur, playing the Macchiavelian war monger Sir Breunor. The play had it’s World Premiere in 2009 at the Edinburgh Fringe and is currently being re-rehearsed for an open air run in a castle in September. It is then likely to be touring all over the UK in 2011.

Allan is absolutely delighted to have joined the Outlander universe and hopes he can live up to the expectations and fluttering hearts that Jamie’s words have set over the years — if all else fails, he is at least a 6’4″ redhead who regularly wears a kilt and whose nose is slightly too long…so at least he’s got that part of Jamie covered!

Sue Robertson (Claire)

(sorry, no picture available yet!)

Sue started on stage at the grand old age of 16 with Dundee Operatic Society (DOS) with whom she has played many principal roles over the years such as Nancy in ‘Oliver’, Minnie-Fay in ‘Show Boat’, Adelaide. in ‘Guys & Dolls’ and Millie in ‘Thoroughly Modern Millie’. Sue has also had the privilege of working alongside playwright Mike Gibb playing the part of Grace on four occasions during 2005 – 2007 in theatres across Scotland in his musical play ‘Five Pound & Twa Bairns’ and Barbara in ‘Sunday Morning on Dundee Law’ which Kevin Walsh wrote the music for. She has also been in the ‘The Steamie’ playing Doreen in 2002 and again in 2004. Sue has recently enjoyed playing the ‘mad’ role of Helen for the second time, working with the cast of ‘The Berries – Twa an’ a Half Pence a Pund’, written by her husband Dundee author, poet and playwright Gary Robertson.

July 31st—that’s THIS Saturday!—is “Tartan Day” in Aberdeen. Which would naturally be cause for great excitement on its own [g]. However…

This Saturday is also the Official Launch of OUTLANDER: The Musical, with three live showcase performances of songs from the show. Mike Gibb, lyricist and producer of the show, says:

“The showcases are in the Drum Aisle (where the ancient “Drum of Irvines” were buried) of St Nicholas Kirk in the centre of Aberdeen at 1.00, 2.15 and 3.30 on Saturday. Admission is free. Any Gabaldonians wanting to come should email me (info@hamepages.com) so I can reserve seats. Reckon all will be “sold out” as it is at a Scotsman’s favourite price! Lots of overseas holiday makers over here just now as well and an article going into the local press on Thursday.”

Those of us not fortunate enough to be in Aberdeen this weekend are promised later video of the event, though! If that works out, it’ll be up on the OUTLANDER:The Musical YouTube Channel as soon as possible.